Compassionate Care

Learning from exemplars in global health to promote human flourishing

In 2020, Templeton World Charity Foundation announced a bold, new commitment to support research on human flourishing. The Focus Area for Compassion and Ethics (FACE) at The Task Force for Global Health was one of 11 inaugural awardees, working alongside colleagues at Harvard University Human Flourishing Program, World Health Organization, University of Calgary Compassion Research Lab, Leapfrog to Value, and Emory University.

Our work aims to understand how compassion alleviates suffering and promotes flourishing in healthcare settings.

One component of this work includes learning from exemplars of compassion in healthcare settings around the world. This series of vignettes paints a landscape of the insights we've uncovered through interviews with seven organizations. In sharing these learnings, we hope to catalyze dialogue about how we might cultivate compassion more broadly in global health to foster human flourishing.

Insight 1:

Compassionate care means caring for the whole human.

Each story of these compassionate exemplars in global health begins with a single seed. A single seed that moved an individual to take action to alleviate the suffering of a fellow human being. And repeatedly, we learned how these organizations, rooted in an initial motivation to address a singular issue, grew to encompass the needs of the whole human.

For Robert Kalyesubula, founder of ACCESS Uganda, the seed was planted at the tender age of eight, when the Luwero war in Uganda claimed both his parents. The African Children's Choir Orphanage took him in, showed him love, and gave him the education he needed to pursue medicine.

At age 26, he emerged from medical school with a fire in his belly to pay forward the kindness shown to him as a young boy. He took special interest in a 30-year-old woman who kept returning to the hospital where he worked with various illnesses. He learned she had HIV.

Then Robert learned more of her story: She had migrated from Rwanda during the genocide, making a new home in Uganda with her husband and three children. But her husband died after settling in Uganda. And her two youngest children also had HIV and were often sick.

When Robert learned that this woman's stepson stole the land her husband had left her—the only asset she had—he pooled his money with a friend to buy her piglets that she could raise to earn an income. Within 7 months, she had 11 piglets. After this success, Robert realized he could help many people living with HIV/AIDS (PLWHA) in this way. And so, ACCESS Uganda was born.

Compassion is making sure others live well. Like we would want ourselves to live.

In establishing ACCESS Uganda, Robert quickly expanded his clinical concern and care for this woman to also address her economic needs. At the time, HIV drugs were not widely available, so the diagnosis was a death sentence. ACCESS Uganda soon realized that caring for PLWHA was not only about the sick person, it was also about caring for their family and helping them plan for their death.

So ACCESS Uganda began helping their clients create memory books to leave behind for their children. And they helped them plan who would care for their children when they passed, and supported children orphaned by HIV/AIDS. They even trained community health workers to assist in these efforts. "It was a need you could not ignore," Robert said.

Other organizations we interviewed told similar stories. At Shevet Achim in Israel, they not only connect children to lifesaving surgeries, they provide communal living for families seeking care. At Tribal Health Initiative in India, after establishing a hospital for an underserved indigenous populations, the founders expanded their offerings to agriculture, income generation, and education. And at Friendship in Bangladesh, a floating ship hospital grew into holistic programming that responds to the broader needs of marginalized communities, from climate adaptation to poverty alleviation to empowerment.

Through all these organizations, we've learned that compassionate care goes beyond a medical focus on a specific ailment to one that sees and cares for the whole human.

Insight 2:

When you heal one person, you heal the world.

There's a difference between treating the medical conditions of individual persons and providing care so that entire families and communities may heal. Compassionate exemplars recognize this difference and organize their delivery of health services to achieve it.

Dr. Kazi Golam Rasul, Director and Head of Health at Friendship NGO in Bangladesh, describes it this way: "When you repair even one cleft palate or one club foot, I tell my team that you impact up to 100,000 people." His team provides health services to the remote communities living on the shifting sandbank river islands (chars) in Bangladesh.

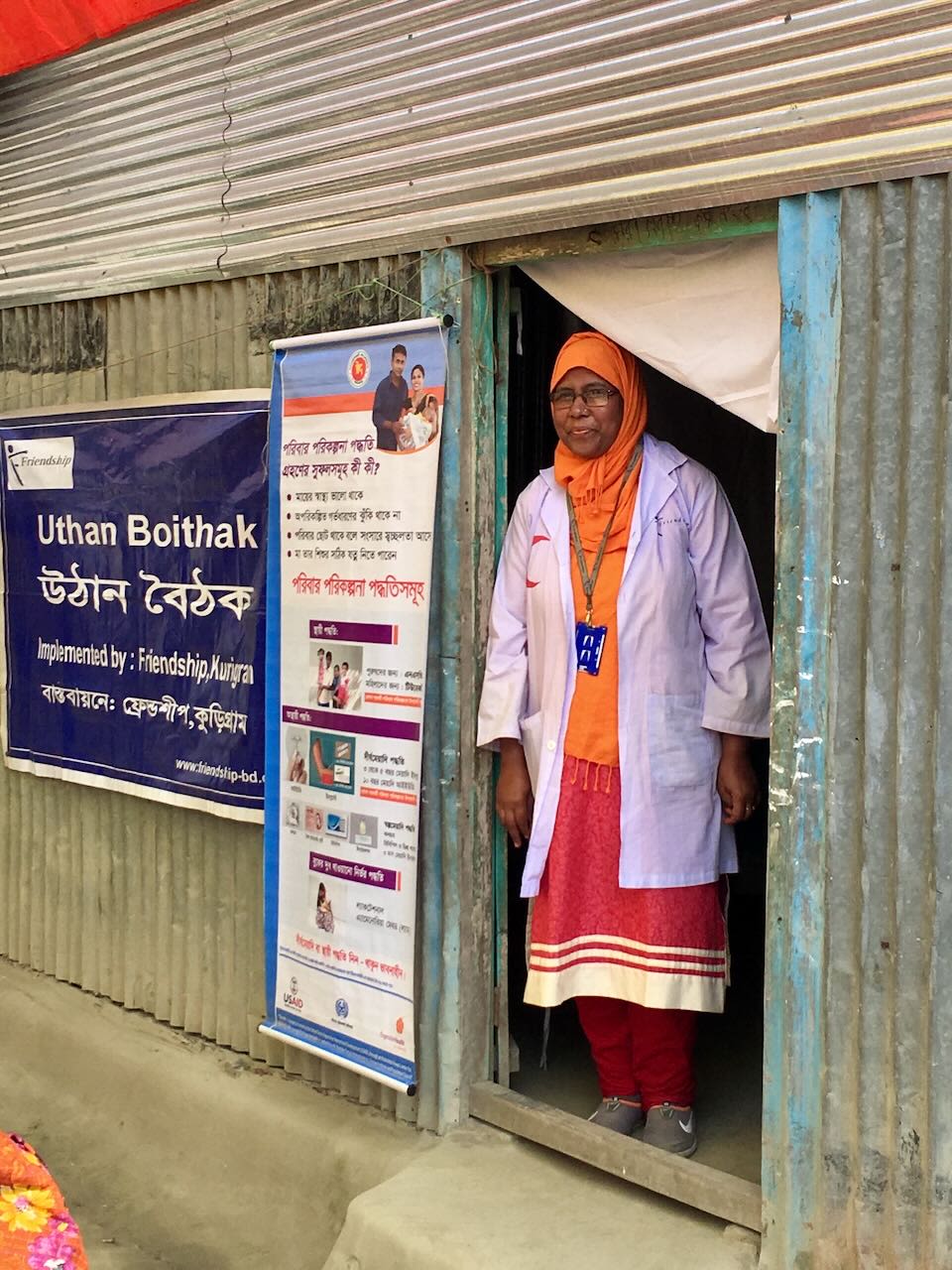

Friendship began its operations in 2002, pioneering the first NGO-run hospital ship in the world for these marginalized communities. They soon realized that centering community interests and having lasting impact meant they had to holistically address the social issues facing these communities.

For example, many people in the char communities live with easily curable conditions, like cataracts, but they suffer, often neglected by family members, because they may not have money for transportation or someone to accompany them to the health facility.

Friendship reaches these individuals through mobile medical teams, conducting satellite clinics on a weekly, bi-weekly, or monthly basis at low- or no-cost. Small static clinics staffed by trained paramedics also offer basic treatment, free medicines, and hygiene and nutrition education.

These efforts not only extend access to healthcare in these isolated communities, they also deepen the organization's relationship with community.

Another social barrier to healthcare in the chars is stigma. Many rural Bangladeshis consider congenital anomalies, like cleft palate and club foot, to be a curse from God. And if the child is a girl, the community may ostracize her and her family.

Friendship trains community medic-aides and skilled birth attendants. As community residents, these women not only deliver basic community health services to every doorstep. They also build trust and establish a consistent presence, enabling Friendship to deeply listen and understand communities and address stigmatized conditions.

We have a deep understanding of the [communities'] problems and offer deep solutions and relief that could not happen if Friendship wasn't there.

Friendship's investment in community relationships and health service design that meets communities where they are helps overcome barriers to care. Dr. Rasul highlights how they save women's lives through cervical cancer screenings and treatments, restore mobility to child burn victims, and give back independence to the elderly after cataract surgery.

"You will never understand the feelings they feel when they see their palates or club foot repaired," he explains. "It brings people joy and independence—it is real empowerment."

But beyond that, Dr. Rasul explains that repairing one person's life-limiting condition catalyzes a ripple effect in their families and communities. For example, repairing a young girl's cleft palate not only addresses her difficulties feeding and speaking. It also removes the stigma from her family, enabling them to reintegrate into the community.

Acceptance. Belonging. Human connection. Beyond health care interventions, Friendship's compassionate orientation is addressing elements fundamental to human flourishing.

"Because Friendship is there, we can free these people from their daily sufferings," Dr. Rasul explains. "With minimal resources, people can live a life with dignity, better opportunity, and hope."

Elderly woman with untreated cataracts

Elderly woman with untreated cataracts

Friendship satellite clinic (Photo credit: Heather Buesseler)

Friendship satellite clinic (Photo credit: Heather Buesseler)

Health education session led by Friendship community medic-aide (Photo credit: Heather Buesseler)

Health education session led by Friendship community medic-aide (Photo credit: Heather Buesseler)

Family in a char village that Friendship serves (Photo credit: Friendship NGO)

Family in a char village that Friendship serves (Photo credit: Friendship NGO)

Insight 3:

We heal in community.

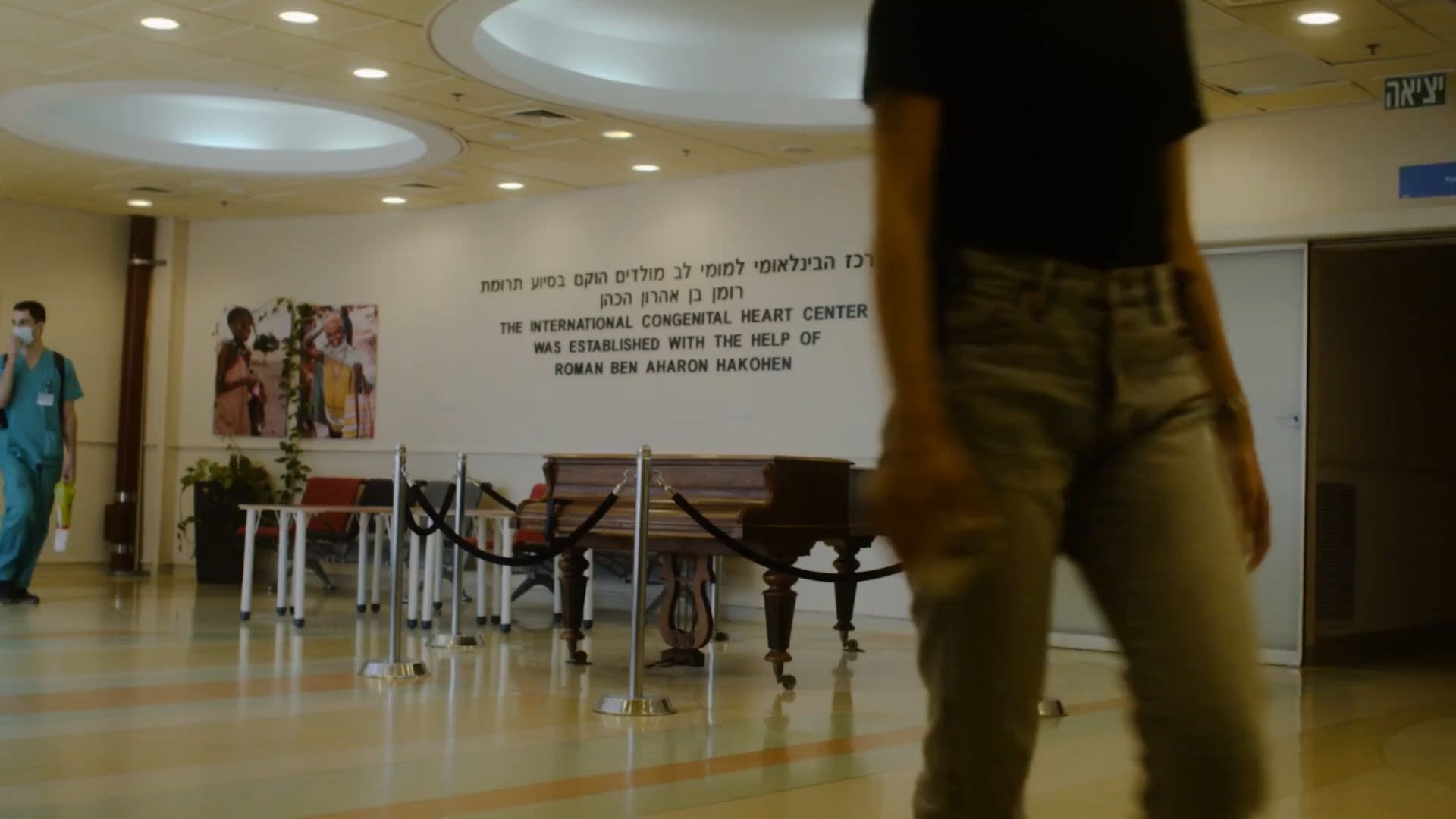

Shevet Achim in Israel was established as a community to express God's grace. Their purpose is to help children with congenital heart defects living in neighboring Middle East countries receive life-saving surgeries.

Shevet Achim acts as a trusted intermediary among families of various faith backgrounds seeking healthcare, immigration authorities of nations in conflict, advanced medical centers in Israel, and a global network of volunteers and donors.

Through great suffering, opportunities are born to bring people together.

Though rooted in Christian values, Shevet Achim works across faith backgrounds and political divides with the shared recognition that every life is created in the image of God, and a belief that no child should be denied life-saving care. From this core value, they work with the willingness and commitment of Jewish doctors at the Israeli medical centers to provide surgery for patients—most of whom are Muslim—in a region of the world otherwise fractured by religious differences.

"It's amazing to see how responding to this kind of suffering draws people together who would never talk to each other otherwise. Everybody seems to recognize the life of a child is sacred."

In addition to cultivating a multi-faith community to save children's lives, what truly sets Shevet Achim apart is the accompaniment they offer to the families seeking care.

The name, Shevet Achim, originates from Psalm 133 in the Bible, which says, "Behold how good and pleasant it is when brothers dwell together in unity." This verse provides the foundation for the structure and character of this faith-based organization.

Organization founder, Jonathan Miles, his wife, and volunteers all live collectively with patients and their families during the operation and recovery period, which can last anywhere from two to 12 months. "This is all about relationships, and that starts in our house," Miles explains.

"We are living together, side-by-side with these families. We start every day by praying, we eat meals together, we all live to the same standard. Very warm and trusting relationships develop between us."

We're made for community. We are spiritual beings.

Miles reflects on how the organization's spiritual center is what makes this accompaniment and co-habitation possible. "If we approached this purely as a humanitarian issue, it would be very different. It wouldn't be what we're doing. If some guy came along with some good ideas about how we should all live together and help each other, I'd expect it to go off the rails pretty quickly. The spiritual piece is everything to us."

"We walk with the families we've been living with and have come to know and love. Rejoicing with those who rejoice and weeping with those who weep is very powerful."

Insight 4:

To flourish, compassion is more important than medicine.

Inspired by Mahatma Gandhi, Dr. Regi George set off on a backpacking trip throughout his home country of India in the early 1990s to find where his skills as a medical doctor were most needed. He happened upon Sittilingi–a remote valley in Tamil Nadu, home to 15,000 indigenous Malavasi people, referred to locally as "Tribals."

The suffering of the Tribals called to Dr. Regi. They were surviving on subsistence farming, dying from easily preventable illnesses, and neglected by the government. So he and his wife, also a physician, decided to uproot from the city and begin providing healthcare for the Malavasi.

Compassion and caringness are more important than the medicines we give. We don't just treat patients – we're trying to improve their lives.

Dr. Regi and Dr. Lalitha knew they would first have to earn the villagers' trust and build a relationship with the community. The doctor couple spent the first four months living in a hut in the village just to get a sense of how people lived. They spent time listening instead of lecturing–learning about what the Tribals considered their most pressing health issues and about their traditional healing practices.

The doctors also viewed the community as a rich resource to be able to improve their own well-being. They began training women as community health auxiliaries and even as staff of the Tribal Hospital they would go on to establish. Over 80% of hospital staff now are from the Sittilingi Valley communities. Working with and through trusted members of the community earned villagers' trust in these physicians and their hospital.

And as trust in the Tribal Health Initiative hospital began to grow, the issue the community had been most concerned about–infant and maternal mortality–began to decrease. Infant and maternal mortality in this area are now among the lowest in India.

"We are a hospital for the Tribals," Dr. Regi emphasizes about the non-negotiable values of Tribal Health Initiative, "Therefore, Tribals have the most important place in this organization."

"Everyone knows this is a hospital you can come to and no one will be refused. Not because of ability to pay or HIV-status. LGBTQ individuals can come and get treated without stigma. People are not discriminated against," Dr. Regi states. This commitment to welcoming all keeps community members returning for care.

Hospital staff are even willing to unlearn their own Western biomedicine approaches to prioritize patient values. In one example, a patient arrived with a broken finger but wanted to treat it using herbal medicine. The attending physician at Tribal Hospital showed the patient his X-ray and explained that herbal treatment would work but still leave him with a bent finger.

Dr. Regi comments, "For the Tribal person, that deformity is not a problem. In Western medicine, it has to be straight. We are taught that a deformity is a big thing, therefore, it should be corrected. The patients are never asked, 'What do you want? Does a small crooked finger mean anything to you?' If it doesn't mean anything to him, why should he get it repaired? He still goes back to work. He is happy, so therefore, I am happy."

I don't think it's the drugs that make the difference. Most of the healing takes place in the communication.

Compassion and radical community-centeredness continue to be the central organizing force for Tribal Health Initiative. This is what attracts the people of Sittilingi to the Tribal Hospital–not just the services or medicines they make available. Moreover, Dr. Regi and Dr. Lalitha have become a part of the community itself, and in so doing, engendered a reciprocal, lifelong relationship of flourishing with the community.

Summary:

Caring for the whole human. Understanding that healing one person helps entire families and communities flourish. Spiritual accompaniment through the healing process. Centering compassion and the community needing healthcare. These learnings begin to deepen our understanding of what really matters to people when it comes to alleviating suffering and enabling them to flourish.

We continue to interview and learn from more exemplars of compassion in healthcare. We will share their insights in an upcoming installment.

Check out Part 2 of this series!